EMFCTF - Electromagentic Field CTF Write-Up 2018

So it’s come around once again, EMFCamp is an event held every 2 years somewhere in the UK (usually south of England as far as i’m aware) where people from all walks of life come together to celebrate anything that’s geeky/nerdy or just plain cool!.

If you get to go, expect LEDs, Lasers, algorithmically/AI generated techno music, retro gaming consoles. Cool vehicles, crazy constructions, human hacking, blacksmithing, clothes making, recycling t-shirts into cushions… you name it, it’s probably available at the camp. It takes place over a 4 day period (arrive Friday, leave Monday) and is welcoming to all.

I’ve been back in 2016 on my own and managed to make friends with the EMFHam group a few days before I went to have a place to pitch my tent and some people with similar interests to go and hang with in their village. I loved it! it was absolutely brilliant. This year, I neglected to plan ahead and didn’t book off the required leave so couldn’t go in person.

But… the EMFCTF was running and accepting remote applicants so about 6pm on Friday night as I’m about to pack up after a clinic day in work (we do internal conferences three times a quarter) I realise this, quickly register a team as an individual participant (Team: Solomonkey) and get involved.

After a brief twitter interaction to get an account activated (I needed a flag you could only acquire if you were on-site) I was on my way.

Know Your Packets

I’m not going to write these up as it was a pretty easy series of challenges. Most of the issue came from having to interpret what you were seeing to determine the flag. I did like the spam transfer service and the brain melter however, they were fun challenges to figure out, a little bash scripting was required too 🙂

Crack Me

Again, pretty simple series of challenges the one that caused me the most hassle was the one that required film trivia knowledge, I took the hint and still didn’t get it for an entire 12 hours due to a capitalisation issue with my flag submission. I think I pretty much submitted almost the entire script of the movie by the end of it.

Binaries

Here’s where the write ups start. Only 3 as I never did get the 4th one before the scoring time of the CTF ended.

Diff me if you can – 10 points

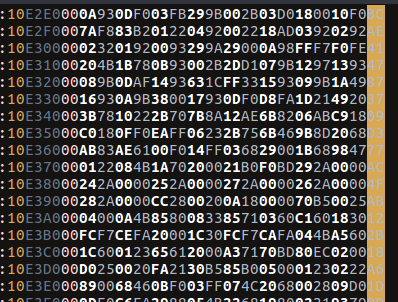

Two files were provided, diff-me-if-you-can-1 & 2.

I don’t generally do much ELF reverse engineering or debugging so I was already on the back foot. My first port of call with any binary is a quick grep/strings of the thing.

In this case the binary is rather small and this is a quick process.

$strings diff-me-if-you-can-{1,2}

Very quickly a few things drop out that are of interest within the second binary.

Interesting strings

From the above I can guess that the program is doing something to “decode” the actual flag, but lets go deeper…

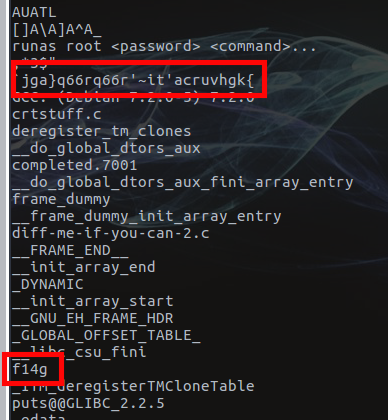

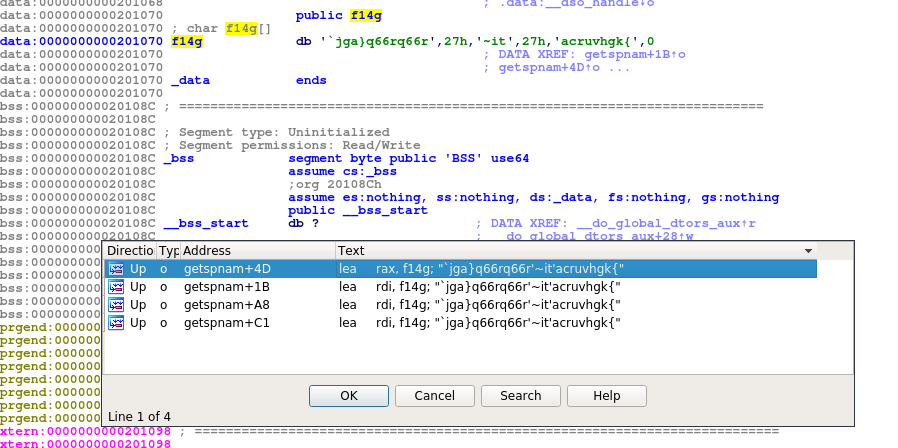

Downloading ida-free7.0 and running it against the binary to view the disassembly and execution flow reveals a few more things. We find the f14g constant and use ida’s “list cross-references” to identify the function within the program that utilises it.

Ida – “List Cross References To”

Bingo. getspnam is our friend.

Classic loop structure

Looking at the tree view for the function we can see a few things, but from a zoomed out perspective we can guesstimate that the following is happening.

- There is some setup where the memory address for the encoded flag is loaded into a register.

- A call to strlen is performed, which returns the string length into a register

- A comparison takes place between some register and the one holding the length of the string

- Depending on that comparison it either loops again or it returns from the function call.

Just from my layman’s understanding of the code here I’m assuming that some operation is done to every single character of the flag and sure enough if we look closer at the left hand branch of the loop we can see an instruction to perform a bitwise xor operation against two registers.

Okay I think we can solve this at this point. We know that:

- There is an encoded string called F14g.

- The contents of which are: `jga}q66rq66r’~it’acruvhgk{

- This is used in a subroutine that performs a bitwise xor against it.

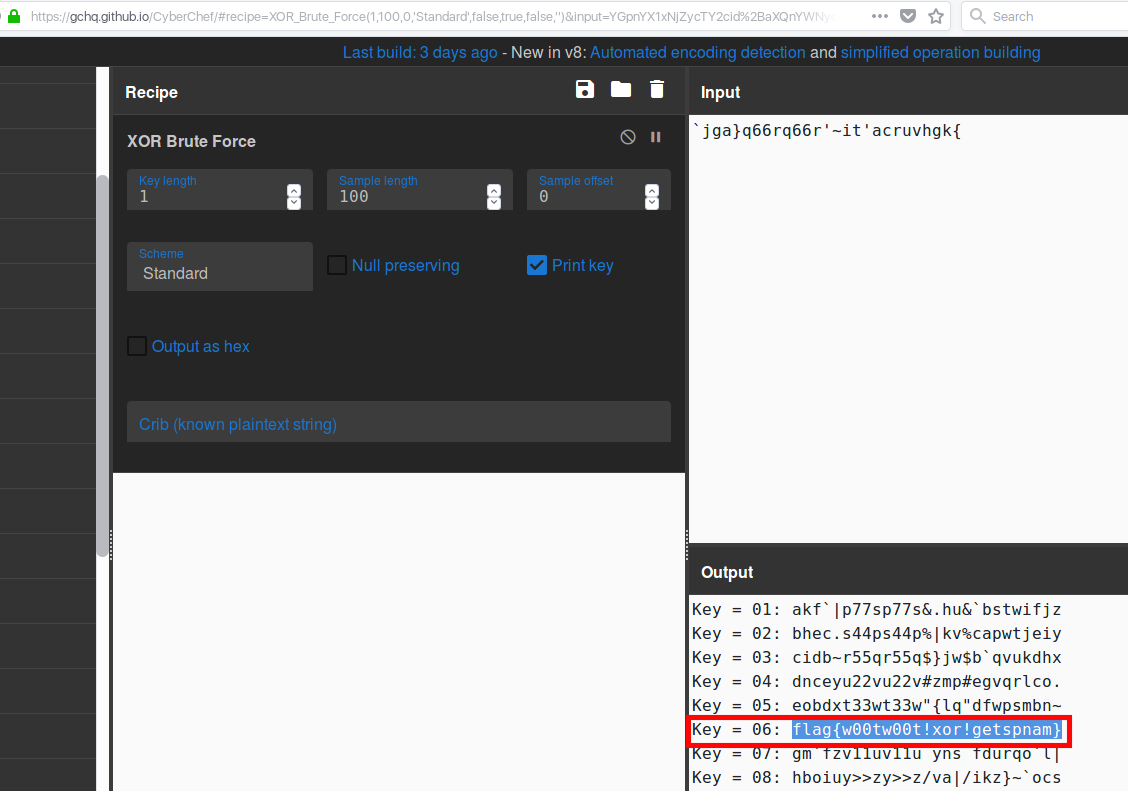

Ask the Chef

So one tool you’ll see me use a lot here is ‘Cyberchef’ an open-source JavaScript data manipulation tool release by GCHQ: https://cyberchef.gchq.github.io

It’s an awesome tool for data manipulation and I use it regularly with work.

One of the functions it has is a XOR brute force feature so lets give that a go!

Challenge Completed! – 10 points to SoloMonkey

Et voila! The flag is revealed.

Reverse Brute – 30 points

Lets move onto a 30 pointer, bit of a jump from the previous but lets go.

We’re provided with a single file this time, a .so this file extension denotes a shared library, similar (in layman’s terms once again) to a DLL in windows parlance it contains resources and functions that can be called upon by other executables… but we don’t have any.

First step as always was strings, sadly no dice for a flag but it did reveal a few interesting phrases surrounding namely: “leakkey” and “keystring”.

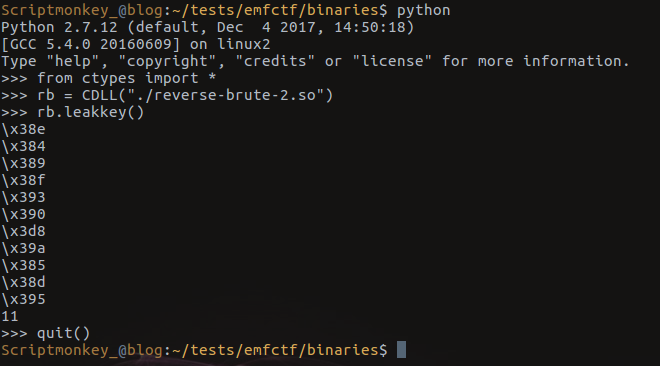

We’re going to have to do something clever with this one. The clue from the CTF web dashboard was “load, locate and trigger the leak”. In my head this means that we’ve got to somehow load the shared library, locate the leaky function and cause it to fire.

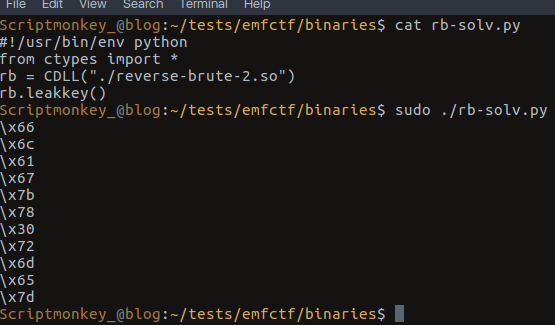

Loading…Triggering…

Lets solve the loading issue first. I initially fell into a rabbit hole of trying to write my own C program to do this, but having never really written C in anger, at least not in the last decade and not being familiar with calling shared libraries either, this was a wasted effort.

Then I recalled something from a python training course many years ago where we were calling functions from win32 dll’s within python. A quick google reveals the ctypes library is just the ticket and a nice and easy bit of code snippet is given for calling functions in an external shared library on linux.

#!/usr/bin/env python

from ctypes import *

rb = CDLL("./reverse-brute-2.so")

rb.leakkey()

is all that’s needed.

Running the above inside of a python interactive terminal results in:

Output! WOOT!

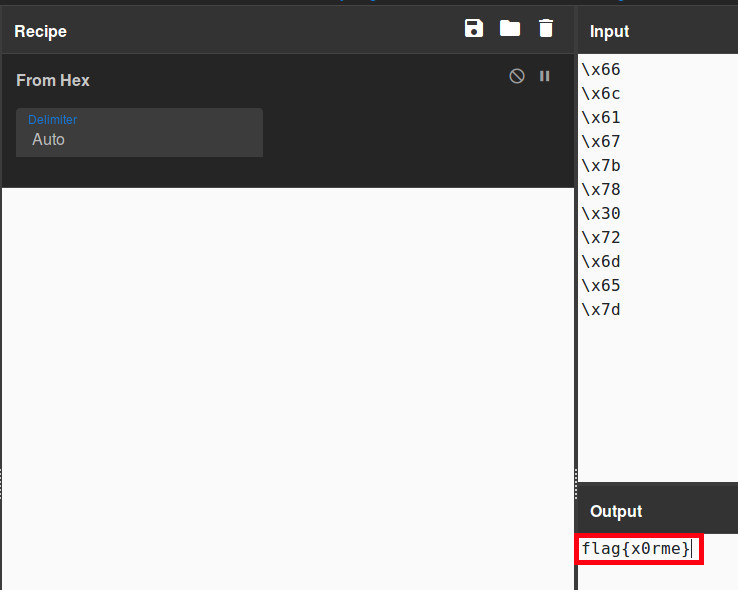

Okay we’ve got ourselves some data. So I headed off to my favourite data manipulation tool once again and attempted to solve the issue. Only right from the off my spider senses should have been tingling, these aren’t anywhere near printable ascii characters (some are unicode printable, but nothing meaningful) and many hours and failed flag submissions later, we’re no closer to finding the issue.

Back to the Code

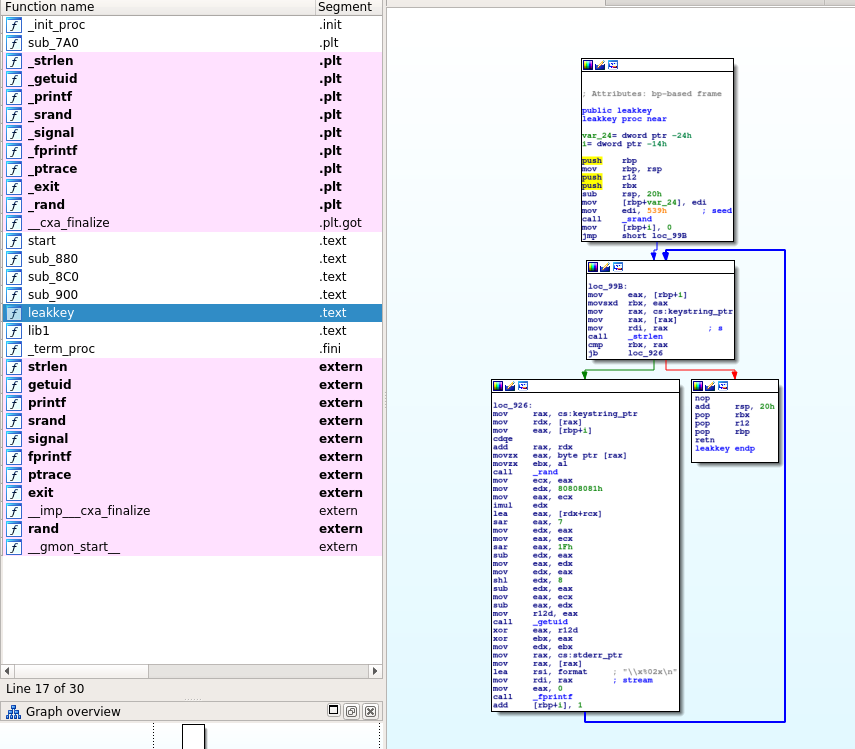

Lets fire up IDA one more time and have a look at what’s inside.

‘Leakkey’

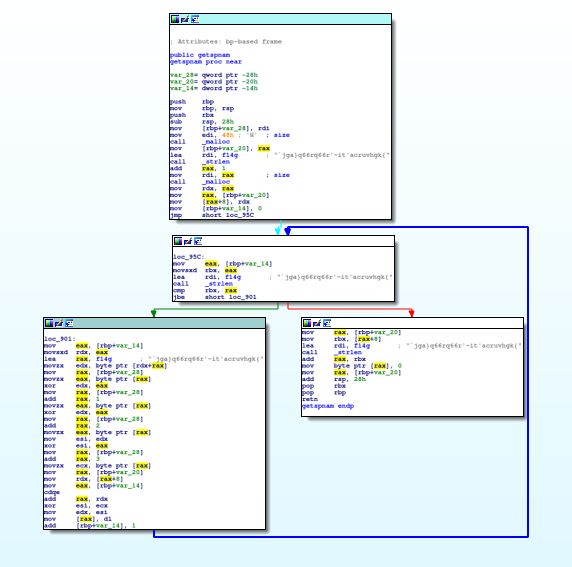

So we see the ‘leakkey’ function listed on the side and if we view that in tree view once again we’re seeing this classic loop structure. Applying the same reviewing steps we can see the following happening:

- Some setup occurs where the string length of a constant referred to by “keystring_ptr” is taken.

- This is used in a comparison to determine whether or not to loop.

- If its not equal, it performs several operations to it

- calls _rand

- appears to use static values of ‘80808081h’ and ‘1Fh’ for something

- shift left 8 bits – Just from using my head I’m assuming this is iterating through each character/byte in a string/array.

- calls _getuid – I initially miss this.

- performs some xor operations, twice over.

- calls fprintf to print out that particular byte.

- adds 1 to the counter and loops.

- If it is equal, it returns to the function that calls it.

So I spend several hours trying to figure this out and getting nowhere (including writing the whole subroutine out on an A4 piece of paper and trying to paper debug what was going on) when I recalled a video by @liveoverflow where he shared some info relating to common tools such as objdump, strace, radare2 and hopper. I remember hopper having a feature of producing pseudocode from the assembly and hopefully making the assembler much easier to read.

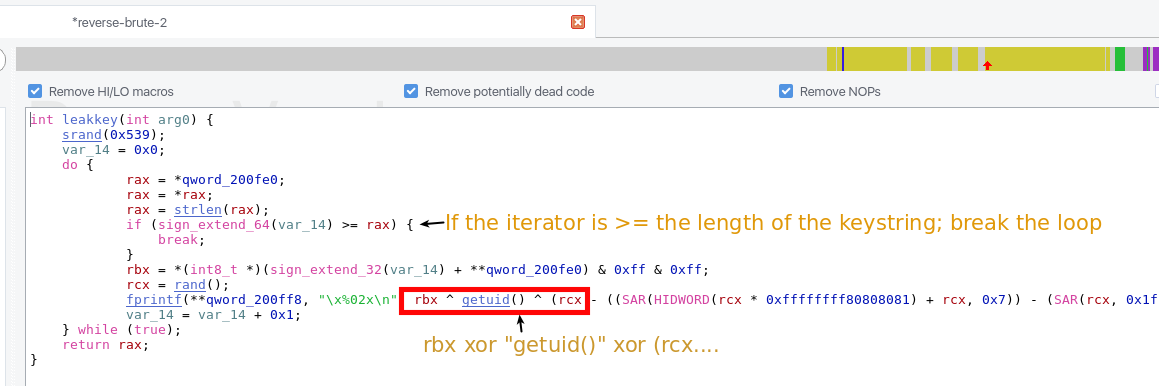

Easier to read

So from the above we can now see clear as day, the output relies upon the UID that the parent process is running as. I’d been missing this call all along, or just dismissing it as not having any effect. Argh! much facedesking occurred at this point.

Linux has very few iconic “UIDs” the most obvious of which is UID 0 for root, but 500 (red hat) and 1000 (Debian) are both also well known for the traditional start of the user space UIDs. We’ll assume its UID 0 as that’s ubiquitous across all *nix systems.

Easiest way of doing this is just running the thing as root so we do just that.

Different Data!

Given the different data we’ve now got we’re onto a winner it seems and these characters, are all ascii printable!

Another challenge solved!

Flag obtained!

Space Invaders – 40 Points

Okay we’re on a roll, well it seems like it from reading the blog post but in reality we’re down to the final few hours of the CTF and I’ve been pulling my hair out for most of it 🙂

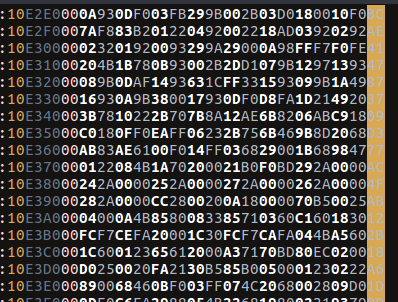

Lets move onto challenge 3. We’re given a single file called “spaceinvaders.hex” and the clue is “this one is weird – what the hell does it run on for a start”.

So we open the file. It looks odd. Sort of like a hex-dump file but not quite. The colon is in the wrong place, there’s no spacing and the memory addresses (or what I’m assuming to be addresses given its just all smudged together with the data) appear different to what I’d expect.

wtf is this?

So I have to admit, initially I thought it was just a malformed file and I tried reformatting things and altering it using sed/awk to make it more “hex-dump” like, I got bored and frustrated with no real success and decided to wing it.

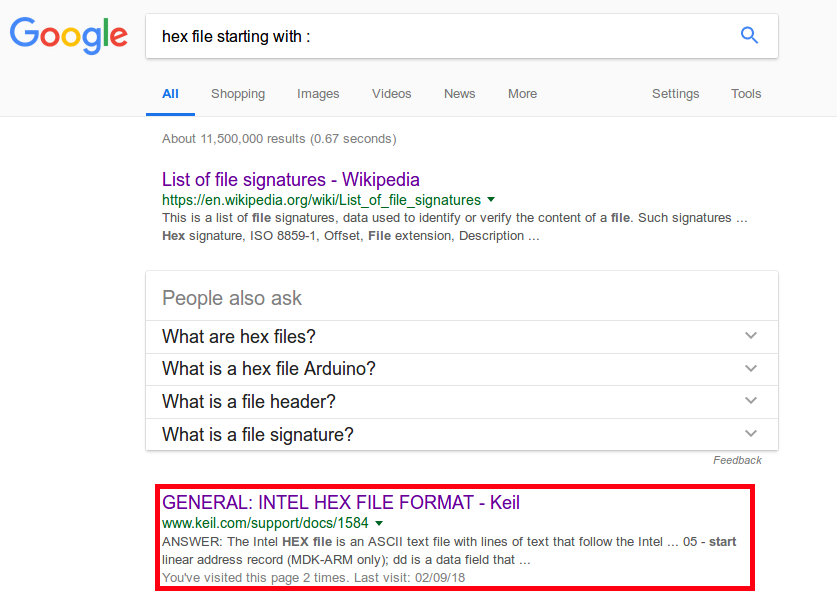

Lets google: “hex file starting with :”

Oh… interesting.

So a click or two later and reading the documentation I see a few things.

This matches our format on a line basis The file ending ends as stated in it too I think we’ve found our file-type. Now how to deal with it. Reading the above web page and just under the section that accurately describes our EOF signature/magic number, there is a link that discusses “Converting HEX, Binary, etc file formats”: http://www.keil.com/support/docs/4038.htm

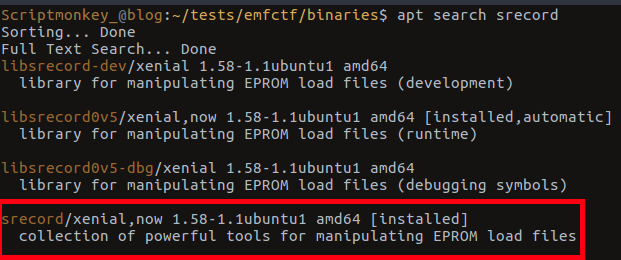

Reading through it talks of windows executables but also of a linux package available from sourceforge called “srecord” a brief apt search comes up trumps and there is already a package in the ubuntu repositories for srecord!

SRecord found in Ubuntu Repository!

A brief install and we’re left with a few executables that are preceded with the prefix “srec_”.

One of these “srec_cat” appears to be used for concatenating Intel hex files together, only by default it seems to be configured for a Motorola EEPROM format, we don’t want that. We want Intel format.

After scouring through the man file for a bit, and a little trial and error, the line we’re after is:

srec_cat space-invaders.hex -intel -output space-invaders.bin -binary

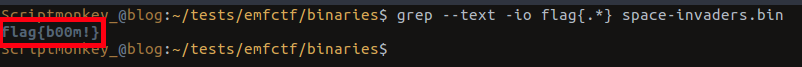

Now with a binary file, we can go back to our default mode of handling binary reversing, lets use GREP! – What? you were expecting strings?, well Grep does support binary files and now after submitting flags previously we definitely know the flag format, it saves us having to scroll through a bunch of string output 😉

grep -io --text flag{.*} space-invaders.bin

Take that evil aliens! 🙂

And that’s the final flag we managed to obtain for the binary challenges.

The End?…

So no. There was one more challenge called Das Uboot remaining in the binary pile and I failed to beat it, in the end only a single team “Never Try” actually did solve it.

Sploity challenges? Nope, I had a quick look at them but they came up right at the end of the last day and I got nowhere, given they are remote network services, I probably won’t get to write those up and hope to read write ups from the teams that did: GraceHoppersPosse and Never Try.

One thing I am relatively sure of is that I probably didn’t solve any of these challenges in the intended manner. I approached it from the perspective of someone unfamiliar with the use of debuggers and reverse engineering on Linux and got lucky.

Ultimately in a CTF, the journey doesn’t matter the destination does. What I can tell you is that these few lines of solution do not include the HOURS and HOURS spent smashing my face against them. I spent most of the 3 days trying to solve these and I learned a hell of a lot in the process and that’s what this is to me. An opportunity to educate myself and practice topics I generally don’t make use of in my typical workload.

How do I think I did?

So its difficult to judge, I was doing stuff in this challenge that I’ve not really played with before I’ve learned a hell of a lot about interrogating binaries on Linux and my wireshark-fu is through the roof after completing all the “know your packet” challenges.

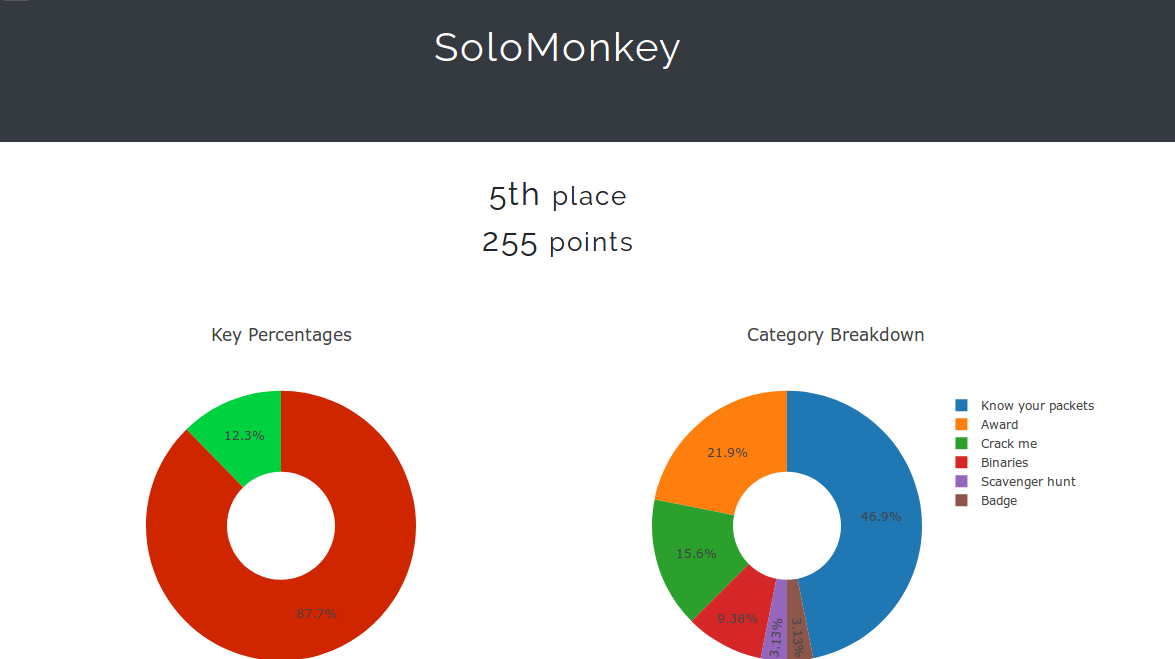

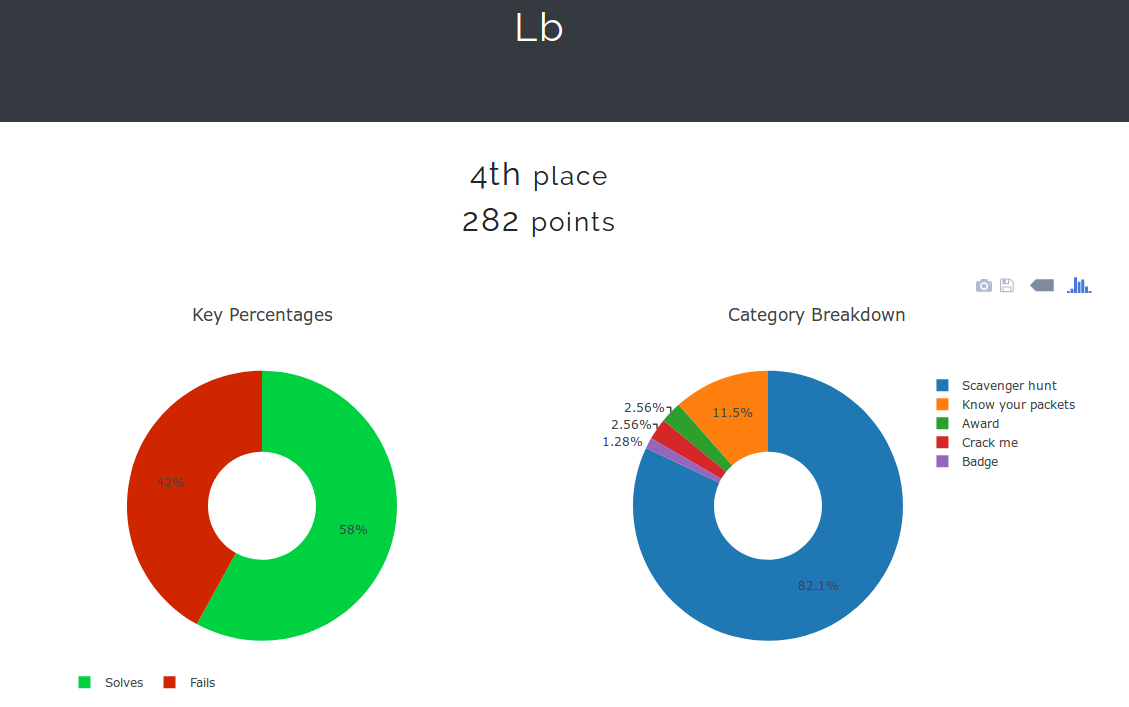

I was also just one man against teams where multiple people were in play. I ultimately finished 5th overall after being pipped to the post for fourth by Team LB in the final hours of play.

Additionally, these teams were all on-site and able to compete for the 237 marks up for grabs in the scavenger hunt. There were several times when I wished I was on-site during my downtime so I could go for a walk and still score 3 points for each scav hunt flag I completed.

If you look at the breakdown between myself and the 4th place finishers Team LB it becomes more evident how much I lost out by not being on-site. Lesson Learned – ALWAYS buy tickets for EMFCamp ;).

Only off-site challenge points obtained (aside from account activation flag)

~80% of their score from Scav Hunt flags

Despite all the above however, I learned a hell of a lot from this CTF and would highly rate it for anyone to have a go, it was great fun to participate in and I’ll definitely be back again next year, this time hopefully alongside a team of people and being able to participate in the on-site challenges.

“Award Points”

Ugh!!! So I took the hits with hints in this CTF. Very often I’d get to the end of a challenge and still not be able to submit a valid flag and I’d take the hint. In every single case except 1 (the film trivia crack) the hints given were of no use to me given where I was in the challenges. It’s a chance and decision you have to take/make on a coinflip but I basically threw away 21% of my score to hint penalties which I really shouldn’t have taken.

All that’s left to do now is extend a huge “Thanks!” to the organisers of @emfctf who I believe are a team from Cisco Security, what once was Portcullis/Portcullis Labs.

Cool things you need to check out

LiveOverflow – This person regularly posts “how-to” videos for reversing, crack-mes, ctf challenges. I’ve learned basically almost all the techniques I performed above thanks to their videos.

https://www.hackthebox.eu – awesome hacking challenges and VMs perfect for practising your skillz 😉

blog.scriptmonkey.uk

blog.scriptmonkey.uk