PeSKy VPNs - A lesson in IPSEC and IKEv1

Introduction

So every quarter my company arranges an internal “conference” where the members of my team have to come up with some sort of presentation discussing research or learning that they have done in the past 3 months.

Often this presentation is written in the last few hours of the last day left and scraped together in a panic, however this time I found myself with a topic of particular interest that I needed to know more about.

I’m a penetration tester, a jack of all trades if you will however my strengths I would say primarily lie within web application security or circumventing client lockdowns.

My network-fu leaves much to be desired and I will say it is one of my weaker points.

So please forgive me if indeed this post is teaching you to suck eggs or appears to be rather low brow for a working penetration tester, this field is by no means my forte and this post is about something that actually I don’t see too much of and ultimately is a result of being bucket-dunked into a world of pain and wanting to actually improve my knowledge to a degree where it’s no longer as painful.

It is an amalgamation of a series of blog posts, with most of the information coming from the chaps at spiderlabs - who have now in the time I took to write up this post, released part 3 of their post on cracking IKEv1 and it’s a cracking read, highly recommend it.

So onto the content…

Finding the damn things

IPSEC VPNs traditionally run on UDP port 500. The use of UDP is an important factor here as UDP based services don’t have to offer any feedback or indication that they’ve received stuff (UDP/IP networking 101). Worse still the RFC for this states that IPSEC VPN endpoints can quite happily drop whatever they do get on the floor if they don’t like it and will silently do so.

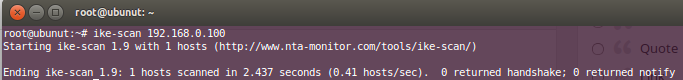

So send the wrong stuff and you could end up seeing:

VPN where are you?

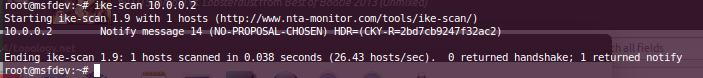

That outcome appears to be either a special configuration or due to a particular vendor’s implementation. I have seen it in the wild but traditionally this happens:

Ah… there you are VPN, but why won’t you shake my hand?

I receive a notify message. Notify in the world of IPSEC VPNs tends to mean (at least in my research) one of two things.

- It doesn’t like the “transform” you’re using to communicate with it.

- It doesn’t like you – it may have an access list associated with it and you’re not in it so it will not negotiate a connection with you.

If it’s number 2 in that list, you’re on your own. I’m interested in the case of number 1.

What is a Transform?

A transform is a series of “instructions” that specify things like:

- Encryption method

- Hashing Algorithm

- Authentication method

- Diffe-Hillman Group ID

What those things do is somewhat unimportant for the purposes of this post however all you do need to know is that these are typically specified in terms of numbers on the command line.

For example:

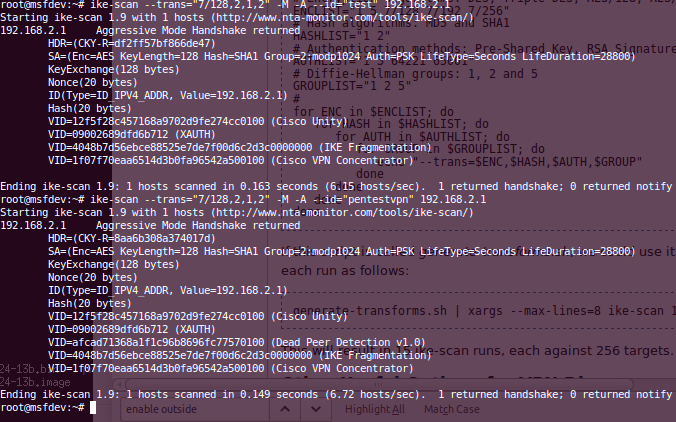

AES 256, SHA1, PSK Auth, DH Group 2 translates into --trans=7/256,2,1,2

ike-scan is old

So our main problem is that ike-scan comes from a period of time (2003-2007) where AES support on VPNs does not appear to have been widespread. In fact much more common was the use of DES and 3DES encryption and as such ike-scan’s default scan setup scans for exactly that.

So now we know this lets follow ike-scan’s own guidance (available at their wiki: http://www.nta-monitor.com/wiki/index.php/Ike-scan_User_Guide) and script ourselves a brute forcer.

The next bit of code will generate EVERY transform listed within the nta-monitor wiki, however as the wiki reveals each transform is a 16bit unsigned number, giving you 65536 possible values across 4 parameters, resulting in 18 million trillion combinations (65535^4) or 18000000000000000000 (20 digits long) for those who prefer actual digits so it’s somewhat unreasonable to smash that many transform requests across a network connection not forgetting the fact that the vast majority of numbers in that list are likely to not be implemented as anything so the guideline in the wiki (generated from the RFCs concerning implementation of VPNs) is as good a solution as any.

for ENC in 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8; do

for HASH in 1 2 3 4 5 6; do

for AUTH in 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 64221 65001; do

for GROUP in 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18; do

echo "--trans='$ENC,$HASH,$AUTH,$GROUP'" >> ike-dict.txt

done

done

done

done

And now you have a dictionary of 10,800 transforms to throw at any VPN you may come across which should increase your chances of success.

Using the dictionary effectively

So bare with me on this one. If speed is your thing, the wiki suggested method is probably best. With my virtualised test rig of an ASA 8.0 box I can smash ~150 transforms in a single proposal and it’ll respond properly, reducing the actual number of network requests to 72.

cat ike-dict.txt | xargs --max-lines=150 ike-scan -M <target_host>

However if it’s a local network I like to encapsulate it in a while loop. It’s rusty and greatly adds to the time for testing (takes something like 3 minutes instead of 1) but it simplifies things when you don’t have the necessary lookup tables or cannot be bothered to figure out the syntax to recreate the handshake once your discovery scans are completed.

while read line; do

echo ike-scan -M $line 127.0.0.1

ike-scan -M $line 127.0.0.1

; done < ike-dict.txt

Yep it’s simplistic and dirty but hey a simple double grep then just gets me the line I want.

grep -B7 "1 returned handshake" ike-output.txt | grep "--trans"

Being Overly Aggressive…

So the truth of the matter is that the above does Main Mode handshakes which to my knowledge are invulnerable. However my knowledge extends as far as google fu and the NSA handbook (Network Security Assessment Vol 2, not the National Security Agency) so feel free to correct me in the comments if you’re wrong, this is as much a learning exercise for me as it is for anyone who is reading this trying to figure things out.

While I’ve only ever seen machines responding for the same transforms regardless of Main Mode or Aggressive Mode, according to my research I’ve discovered that a machine may respond for a different transform for each method. So in truth the only way of truly discovering all possible Aggressive Mode capable VPN endpoints is by scanning with -A. Unfortunately this will greatly slow down your scan taking at least 2 seconds per connection so I would advise only using the wiki based method for that.

Assuming you’ve now found yourself a VPN endpoint that responds to aggressive mode handshakes. What next?

Cracking Hashes

Pskcrack tends to be the tool of choice in most of the online articles you’ll read online. People favour it for bruteforcing/dictionary attacking the hashes. Fact is, this too is ancient tech.

Based on CPU cycles it struggles when you compare it to ocl-hashcat or cuda-hashcat (depending on the flavour you prefer).

- PSKCrack ~ 100 plaintexts a second were attempted.

- Hashcat (CPU Based) ~ 2000 plaintexts a second.

- cuda-hashcat (GPU Based) ~ 2.6 million plaintexts a second.

Using cuda-hashcat to brute force the resulting hash is clearly the way forward as the optimisations and improvements (including the ability to make use of GPU processing power) far out-perform the traditional PSKCrack route.

Myths and Realities

The common misconception is that IKEv1 + Aggressive mode handshakes are bad, that you only ever receive a valid handshake when you correctly guess a groupid and that using these two things, results in the ability to crack a hash, gaining access to the internal network and therefore Nessus ranks them as a CVSSv2 score of 5.0 suggesting that a partial loss of confidentiality is possible and that difficulty of exploitation is low. This may well have been the case in 2005 but in 2014, 9 years on things have changed somewhat and in my opinion the vast majority of encounters of this configuration will be low.

In order to gain access to a VPN using IKEv1 and Aggressive Mode Handshakes you need the following:

- A working transform (Done as part of discovery)

- A valid Group ID

- …

So we need two things? Not quite. Most if not all VPN instances also employ secondary authentication methods, be that X-Auth, Certificate based or RSA Two Factor Auth. So now we’re adding a second level of complexity, i’m not great at network comms and certificate based/RSA attacks are likely beyond my skillset so we’re skipping that.

If you can do it, awesome. However i’m not the fastest tester so trying to capture RSA tokens across the wire and replaying them before they expire will just end in epic failure on my part. I’ll focus on X-AUTH the weakest of the 3 methods.

So now we’ve established we need:

- A working transform

- A valid Group ID

- A valid X-Auth Username

- A valid X-Auth Password

Having all 4 of the above will finally grant you access to the network behind the endpoint of some sort.

Enumerating Group IDs

So I’ve seen and read countless (even recent) VPN attacking articles that say:

Use a groupID to obtain a handshake, shove it all in pskcrack and use the psk to connect to the network

The problem with that is that since 2005 Cisco has been patching group ID enumeration vulnerabilities.

Prior to 2005 – Only a valid Group ID would return a handshake. This is known as CSCeg00323 and is now patched on pretty much all systems you would come across. Despite this, searching for “VPN” attacks will often result in this being overlooked and the demonstrations you find will ignore the fact that this has been fixed.

Now with or without a valid group ID a handshake is always returned. If the ID is invalid (as is likely to be the case when brute forcing) the handshake and the resultant hash is generated using a random password (in some cases null), which if cracked, will get you no closer to gaining access to the hallowed network.

So we move onto method 2 of enumerating group ID’s…

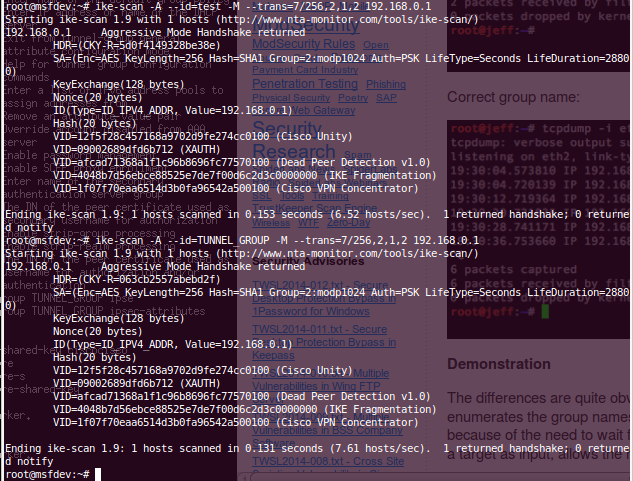

Prior to 2010 – Only a valid Group ID would return a dead peer detection header. This is also known as CSCtj96108 and would result in this contrasting output in ike-scan.

Well that’s a Dead (peer detection) GIveaway 😉

Some tools support this in particular the spiderlabs chaps have a few scripts available at their github that do this detection when given a dictionary of words to brute force.

Additionally the enterprising chaps at portcullis have “iker” which does much the same.

However, this was patched 4 years ago, by making EVERY request return a DPD entry.

Drat! now dead peers are popping up everywhere!

Additionally as it was 4 years ago, that’s plenty of time for hardware refreshes and actual patches/firmware updates to be applied. As your (and mine) mileage may vary with this one we move onto the latest way for enumerating group ID’s.

I have to thank Spiderlabs for all of this as essentially this is their baby, i’m just writing it here in this blog as well a reminder to me and to share the good news.

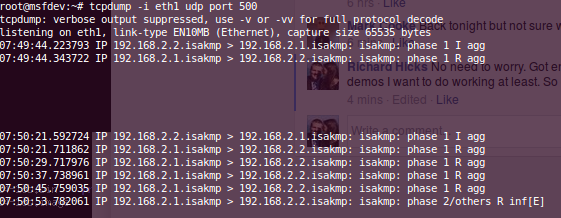

After the 2010 patching of DPD, a person far more intelligent than me decided to see what else might be different between a valid and invalid VPN response and during his research discovered that there were differing packet counts depending on the validity of the Group ID sent.

Are you right? Please be right? Seriously? Are you not the correct ID? aww fine I give up talking to you.

In the case of a valid ID 2 responses would be expected. In the case of an invalid ID, 6 responses would return over a longer period of time (almost as if the service tries incredibly hard to resolve the bad ID).

The major downside with this attack is that it takes time, a considerable amount of time. Those 6 responses span 30 seconds, now there are ways to speed it up (e.g. assume 3 or more responses = fail) but even then it’d still be at 9 seconds per ID attempted.

Additonally, this vulnerability was patched in 2013 as CVE-2013-1194 and I know of no others that replace it.

However the vulnerability above is to my knowledge our last hope of discovering valid IDs on relatively modern kit and to my knowledge the only tool that makes actual use of it is the groupenum.py (note the python extension this time) provided by spiderlabs and available at their github given above. I am unsure if IKER provides the same capabilities, it mentioned “response analysis” in it’s blurb but i’m not sure if that means DPD detection or packet counting support.

A downside to this is that groupenum.py currently only supports DES and 3DES transforms, so in the case of the above AES256 VPN endpoint, there’s no simple script to do it on my behalf.

If I were a master coder of python (or actually did the Python E-Learning package my company has bought for me) I’d have a bash at coding it up myself, maybe you (the reader?) can help out?

Semi-Summary

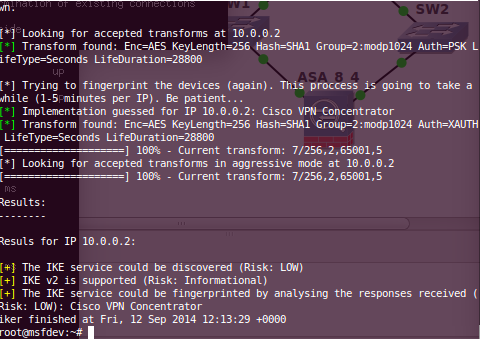

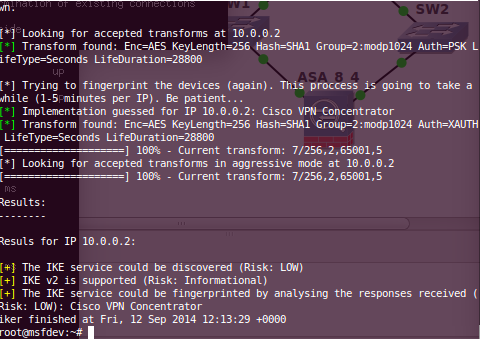

In my opinion i’ve pretty much discounted using IKE-SCAN as a valid tool for finding VPNs and will in future be making more use of Portcullis IKER.

Automated CVSSv2 Scoring too!

Purely because it’s a tool that appears to test a large number more transforms than I believed were present than ike-scan and it automates group ID bruteforcing if you provide it a dictionary using at the very least the first two methods discussed and may in fact make use of the third.

Additionally it automatically scans for aggressive mode transforms too. It is essentially a start, go-make-coffee, review results tool. Perfect for a busy pentester doing a million and one other things in a narrow timeframe.

Continuing on and beating XAUTH…

So our current status is:

We’ve discovered the VPN Endpoint Found a valid transform it is willing to communicate with Using a dictionary we’ve correctly guessed a valid Group ID. If you were to take what was out there on VPN security you would be forgiven for thinking that’s it! We’re in… but we’re not. We still need those X-AUTH credentials.

How do we get those? MitM is the only way I came across (Edit: This has changed, read on for more info). Pretty sure you could brute force them but you don’t even know a valid username for the service so you could be there a fair ol’ while.

So once again the IKEv1 + Aggressive Mode issue becomes even more difficult to break, As you need to be appropriately placed to perform said MitM attack, however assuming there are people logging in from coffee shop hotspots and you’re there too. This is where FIKED comes in.

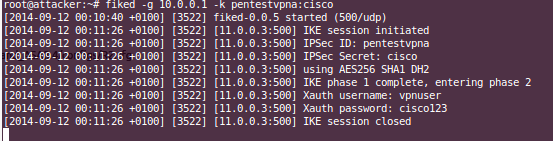

FIKED – Fake IKE Daemon

Using the details you have discovered so far and some arp-spoofing or Wifi pineapple, Jasager/Karma action you can using FIKED set yourself up as a fake VPN endpoint, with the correct group ID, which would complete Phase 1 auth and move the client to phase 2, where the XAUTH comes in.

The client would blindly send their credentials believing that they are connecting to the right VPN endpoint (no certificate checking with XAUTH), et voila! You have captured their creds in the clear.

It’s me! Honest!!!

So in order to get FIKED to work you have to figure out a way of forwarding the victims traffic through yourself. I achieved this by setting up 2 arp-spoof sessions to capture traffic in both directions between target and their gateway.

However, FIKED was the only tool I found capable of performing this MitM attack and despite me having successfully set up arpspoof (tried ettercap too but wanted to rule out weird packet forwarding nonsense), in both directions, with TCPDUMP showing UDP traffic on port 500. FIKED never responded to my requests and VPNC on my victim box would just hang until it timed out never receiving a handshake.

Only by deliberately connecting to the FIKED VPN endpoint could I actually get the screenshot I used above. Colleagues I demo’d this to suggested that it could be that I was using 2 virtual hosts, across a virtualised network causing the issue and that may still be the case. I never did get around to pinning it down despite spending many hours on it.

If you can get this working, please do let me know what on earth I was doing wrong.

Conclusion

Now you have:

- Located a VPN Endpoint

- Successfully obtained a handshake with it

- Discovered a valid Group ID

- Performed a man in the middle attack against a client and captured the XAUTH credentials

Finally, now you can connect and reap the rewards of completing one of the most involved “hacks” you’re likely to complete in your lifetime. If this is a CVSSv2 score of 5.0 then CVSS is even more broken than I thought.

The use of aggressive handshakes is nothing without some context applied, as is the case with most things in the security world but I have seen many reports with it just shoved in with no context applied. CVSSv2 score 5.0.

This whole process was a learning experience that taught me from the ground up some information about VPN’s in particular this variant, but I learned a lot about other subjects as well. It got me comfortable with the ins and outs of some rather complex cisco stuff (at least in my opinion) and let me get to grips with the intricacies at getting Virtual Box working in tandem with GNS3 on Ubuntu 14.04.

It also led to some expensive purchases from Ebay. So if you want a Cisco VPN Concentrator 3000 series with 2 SEP-E modules, dual redundant power supplies and no idea if it works or not. Let me know 🙂

But wait… there’s more!

I mention in a section above about bruteforcing XAuth protection. It turns out the enterprising chaps at Spider Labs have once again been busy and have released a script called ikeforce.py to do just that.

I won’t completely regurgitate their blog-post here as I think I’ve done enough of that above, but if you’re interested in taking this further and proving the risks of IKEv1 Aggressive Mode to a client I’d highly recommend checking it out (Link in the reference section below).

References

Spider Labs – Cracking IKE Part 1

Spider Labs – Cracking IKE Part 2

Spider Labs – Cracking IKE Part 3

… i’m sure i’ve missed some of the more random google search hits I found while researching the above but those are the main contributors to this article content.

blog.scriptmonkey.uk

blog.scriptmonkey.uk